Looking Back: Saybrook, still haunted by witches

As pumpkins and changing leaves signal the end of an orange autumn, and the long black nights of winter descend, beware old hags in high, pointed hats riding broomsticks. ’Tis the fearful season of witches.

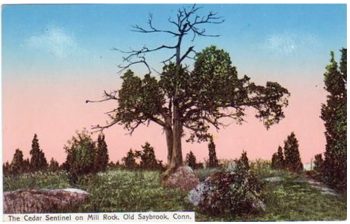

The story is told, not so long ago, about a deep, dark cave in Saybrook that served as the nighttime home of witches. The place was marked by a majestic cedar and was well known to stagecoach passengers as they passed that prominent point known as “Mill Rock.”

In colonial days, settlers cleared the land to plant wheat that would be brought to the nearby grist mill built by Francis Bushnell in 1662. One large tree was left to provide shade for the hardworking farmers. It stood at the top of the hill and was known as the old “Cedar Sentinel.” Nearby was a large rock outcropping and a deep cave.

In those days, to avoid the difficult crossing of the Oyster River, the road wound its way north and past Mill Rock. But, witches were said to be haunting the dark cave, and coach drivers feared passing at night, because witches were thought to throw burning wood on the roofs of the carriages.

When the drivers saw the Cedar Sentinel, they knew they were near the witches’ cave and whipped their horses to speed on by while there was still daylight. Since the witches vanished during the day and also disappeared during the summer, none were ever caught.

In the mid- to late-1800s, neighborhood gatherings were held near here to celebrate the Fourth of July by climbing to the top of Sentinel Cedar to fly the flag. The prominent site also attracted Indians from Killingworth, who came to live in the cave and erect a wigwam where they sold baskets.

The Cedar Sentinel remained for more than 300 years, until a fateful day in 1928 when several schoolchildren carelessly set fire to some branches, and the landmark burned to the ground. Today, only the legend remains.

Quite apart from this legend, Saybrook was one of several Connecticut towns where residents were accused of witchcraft.

When times are tough, humans often look to the marginal members of society to place blame for their troubles — the poor, weak, unpopular or those who are different. It’s an old and comfortable way to deal with difficulty, especially powerful when rooted in faith and supported by popular opinion or respected community leaders.

In the 1660s, there were plenty of causes for fear in Puritan Connecticut — battles with Native Americans, sickness and disease, floods and storms, plus everyday difficulties. These hardships were caused by, well, Satan.

Those having a relationship with Satan were deemed witches. And, in 1642, the Connecticut General Court and Gov. George Wyllys prepared a list of 12 crimes punishable by death, one of which stated, “if any man or woman bee a Witch, that is, hath or consulteth with a familiar spirit, they shall bee put to death.”

For the severely religious colonists, the crime of witchcraft was affirmed in the King James version of the Bible: Exodus 22:18 (“Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live”), Leviticus 20:27 (“A man also or woman that hath a familiar spirit, or that is a wizard, shall surely be put to death: they shall stone them with stones: their blood shall be upon them”) and elsewhere.

The law was first applied in 1647 when Alse (or Alice) Young of Windsor was tried, convicted and hanged for practicing witchcraft, the first such case in the English Colonies.

From that date until 1697, when Winifred Benham of Wallingford was the last to be tried and acquitted, there would be more than 40 cases with at least 11 hangings in Connecticut. The last execution for witchcraft occurred in 1662.

In Saybrook, Nicholas Jennings, a veteran of the Pequot War, and his wife, Margaret, found they were able to live a peaceful life, for a time, after years of turmoil in Hartford and New Haven.

Nicholas was one of the earliest settlers in Hartford, arriving in 1634 with his father, a chimney sweeper. When war broke out with the Pequots, he served under Capt. John Mason and was later given land for his service.

Nicholas began building a home, but gave it up and moved to New Haven, where he was attracted to an indentured servant named Margaret Bedford. As an indenture, Margaret was working off the cost of her passage in the household of a Capt. Turner. She and Nicholas ran off together, but were soon caught. They were brought to court and charged with fornication in March 1643.

They were found guilty, and both were harshly whipped and ordered to marry. Nicholas was also ordered to repay Capt. Turner for items Margaret took, and for the remaining time she was supposed to serve as an indentured servant.

Thinking their troubles behind them, the Jenningses remained for a short time in New Haven and then moved to Hartford to care for his ill father. After his father died, Nicholas and his wife and family moved to Saybrook.

Nicholas and Margaret Jennings were apparently already suspected of witchcraft when, according to the Colonial Records of Connecticut, the General Court in June 1659 ordered that “Mr. Willis is requested to goe downe to Sea Brook, to assist ye Maior in examininge the suspitions about witchery, and to act therin as may be requisite.”

Two years later, George Wood, a neighbor who was unhappy over a land dispute with the Jenningses, accused Margaret of being possessed by Satan. It was an easy charge to make, and Nicholas and Margaret were easy targets.

They were brought to court and tried for witchcraft. The jury was divided and unable to convict. However, the jury ruled that their three children should be taken from them and apprenticed to others. Nicholas Jennings died in 1673. Other members of the Jennings family were among the founders of Fairfield.

Descendants of some of the 11 people executed for witchcraft in the mid-1600s have appealed to Gov. Dannel P. Malloy to issue a proclamation clearing their distant relatives’ names and condemning the prosecutions and killings.

Now eight to 10 generations removed, they are seeking justice for those wrongly accused. Resolutions have been presented to the General Assembly but have not made it out of committee. The governor’s office says he doesn’t have authority to pardon anyone. The state Board of Pardons and Paroles says it does not issue posthumous pardons.

However, descendants are urging the governor to issue a proclamation clearing their wrongly convicted ancestors. After these many autumns it would be a good time to close these cases.

Below are the names, dates, and towns of those executed for witchcraft in Connecticut:

Alice Young, 1647, Windsor

Mary Johnson, 1648, Wethersfield

John and Joan Carrington, 1651, Wethersfield

Goodwife Bassett, 1651, Fairfield

Goodwife Knapp, 1653, Fairfield

Lydia Gilbert, 1654, Windsor Rebecca Greensmith, 1662, Hartford

Nathanial Greensmith, 1662, Hartford

Mary Sanford, 1662, Hartford

Mary Barnes, 1662, Farmington

By Tedd Levy

Special to the Times