Myth and Memory

According to a long standing myth, one young boy who would later become president reportedly chopped down a cherry tree and his father questioned him said that he could not tell a lie, he did it with his little hatchet.

This story about George Washington (1732-1799) is an old myth but he is universally recognized as one of our greatest presidents and his true life story is far more impressive than any myth.

Today, many miss the main point of the story and focus on little hatchets and cherries to prettify advertisements for chopped prices on automobiles and mattresses but it was not always thus and George is worthy of much more.

Under his leadership, a rag-tag band of farmers defeated the strongest military power in the world to establish our independence.

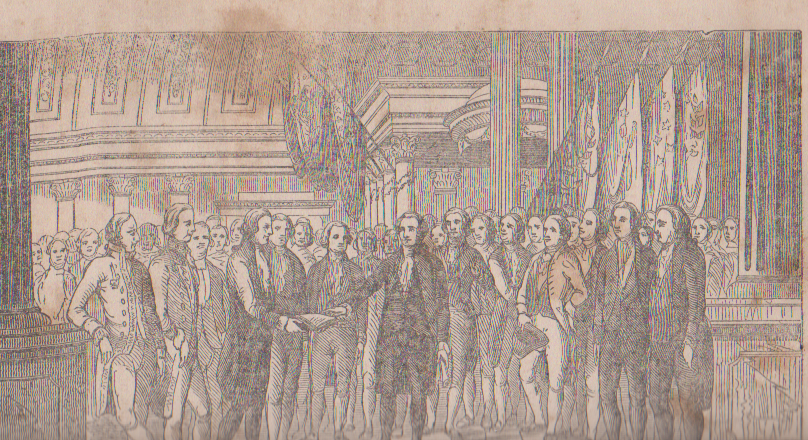

He presided over a contentious and high-powered assembly of delegates to write a constitution that forged a union of states that, with few changes, remains in existence today.

Then, after turning down the suggestion to become a King, he sacrificed his desire to retire to his plantation in Virginia and reluctantly took on the challenging task of leading the new nation.

He was born, according to the Gregorian calendar adopted in 1752, on February 22, 1732 and even as early as the American Revolution soldiers celebrated his birthday. By the early 1800s, the occasion was widely commemorated in the new nation with dances, dinners and parades.

In 1856, Massachusetts became the first state to formally recognize Washington’s birthday as an official holiday and by 1862, in the early days of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for Americans to “celebrate the anniversary of the birth of the Father of his Country.”

There were widespread national observances on the 200th anniversary of Washington’s birth in 1932. His portrait was used on the dollar bill, the new quarter and, along with Lincoln’s in northern states, adorned nearly every classroom. His name was used for towns, cities, and counties, colleges, schools and streets.

Then, in 1968 the U.S. Congress struck. It passed the Monday Holiday Law which changed the federal observance of Washington’s birthday to the third Monday in February. They hoped that having public holidays on Mondays would “bring substantial benefits to both the spiritual and economic life of the Nation.”

The focus of the celebrations changed but rare evidence of earlier reverence remains and can be found in the Old Saybrook Town Hall.

Poised on a four-foot mahogany pedestal, is a plaster model of a grim and trim Washington. It sometimes attracts attention around birthday time but mostly remains an unnoticed part of the interior as hurried visitors have taxes or other issues on their mind.

This bust of Washington resided in the old Town Hall and over time became a bit dusty until First Selectman Barbara J. Maynard white-washed him in the mid-1980s with diluted shoe polish.

The bust was one of several bronze and plaster models created by James Wilson Alexander MacDonald (1824-1908), probably in 1899, and based on the original life mask of Washington modeled at Mount Vernon in 1785 by noted French sculptor Jean Antoine Houdon.

A search of the town records reveals that it was presented to the Selectmen on July 1, 1925 by “Eleonore C. Morin and Lawrence C. Morin, widow and daughter of the late Eugene Henry Morin to whose memory this gift is dedicated.”

So, once again, as a grateful nation enjoys the “spiritual and economic” benefits of Washington’s, I mean the President’s Day celebration, citizens can take comfort in knowing that the event is a commercial success.

So, once again, as a grateful nation enjoys the “spiritual and economic” benefits of Washington’s, I mean the President’s Day celebration, citizens can take comfort in knowing that the event is a commercial success.

In the meantime, I cannot tell a lie, commemoration of Washington’s historic triumphs, like the bust in the Town Hall, remain silent and mostly unknown. Guess it’s just part of the price we pay but there is much to learn from George Washington and our nation would benefit from a true and meaningful observance.

Copyright Tedd Levy